How can a society ask people to know how to embody interpersonal consent when we fundamentally also ask most people to practice nonconsent when it comes to their work lives?

Is consent to sex different than to work?

Choosing what your body experiences, consent, in sexual encounters has a clear bar: the presence of yes equals consent. Anything but that and we begin to step away from clear consent. Situational consent, for example, is when we consent to something in a given context but might not actually want to do it otherwise: politely declining unwanted flirtation to “keep it light” at work, shooting a surprise scene in a movie that keeps our career moving but feels gross at the time, downplaying how we’re treated by people with more power.

The amplification of the crisis of nonconsent at work by the #MeToo movement and many longtime activists is crucial and has lead to outcomes in workplaces, including for example NYC’s February lawsuit against the Weinstein Company.

I am happy to see these conversations and the bar being raised at work, but something is missing for me. We need to add a labor facet to this discussion, because so many people do not fully consent to having work lives to begin with.

For many people the reality of selecting employment was birthed by not having meaningful choices, picking something acceptable enough and dealing with the parts they don’t like, or acting from learned experience in a constrained way as if there aren’t choices. A “grin and bear it” attitude when your boss yells or doing whatever your manager asks of you even if you don’t want to are one aspect of this issue – but to me, the bigger issue is working at a job you wanted to begin with, when work itself is not optional for most. This is where the question of consent *to* work begins.

The kicker: we are, thankfully, increasingly finding ‘ok-enough-I-guess’ unacceptable when it comes to sex. So, why is it normal when it comes to work? Why treat two things our bodies do so differently?

Did you choose or “choose” your job?

For every subway car full of people who must imagine a work situation where you’re able to create exactly the job you want, never ever have to do things you don’t feel like, and only work when you feel like it, there’s maybe one person who’s managing to do that. One – and good on them. The desire for this level of authenticity props up the popularity of the #fourhourworkweek, the #digitalnomad, the #brandyou thought leaders – they know that a need to truly choose our working contribution to the world lives within each of us, yet is denied to most of us when it comes to labor.

For many a fully-chosen work life sounds like a dream indeed, and instead it’s Manic Monday where you have to wake up from your dream from to attend to reality. In a common scenario for most workers, a real work life has “great, for work” or “good enough” or “withstandable” or even “miserable but it pays me” jobs. This plays out in one-employer towns; “choosing” between, say, a fast food chain or a retail outlet, or a corporation or a non-profit where the hours keep you from your kids and passions; picking something because you’re passionate about one aspect of it; believing you can’t get a better job and staying put in a bad situation.

For me, a cis woman coming out of a working-class background, most of the jobs I’ve had were selected situationally and worked tenaciously, with an effort to find whatever connection I could to eek interest or enjoyment out of the work.

Sometimes that was more effective than others.

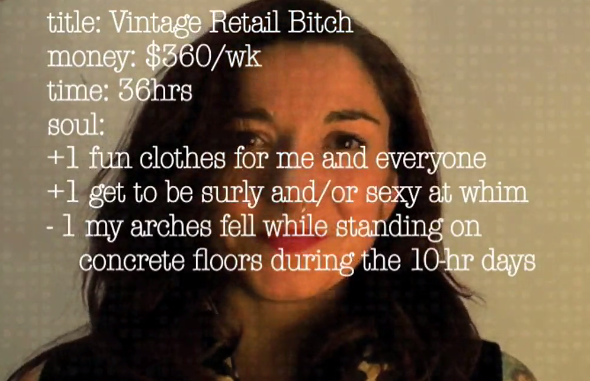

Screenshots from my 2009 video “Working Girl Blues,” playing at the NYC Feminist Film Week this March 2018, lists the jobs I had from ages 15 – 28 giving each a “soul power” grade.

The Ivy League was the worst, by far. I worked there for 10 irretrievable months.

The hope of better choices, to get closer to consentual work, drives people to get degrees, do internships, learn trades and skills, and yes, leave situations that are not good for them. It also can amplify blurry consent by asking people to mediate their “presence of yes” even further: take out a loan they feel worried by, suck up to someone they don’t enjoy, learn to be good at something well-paid but disinteresting to them. If any of this sounds familiar, you’re not alone.

As I’ve moved along professionally I’ve found engaging and interesting things to do for money and it makes a major difference in my daily internal peace. For the strata of workers who are in positions that fully align with their interests and desires, I do not aim to reduce your satisfaction in your work — please do enjoy, you’ve got it as good as it gets for work. I call this second-order consent: choosing your specific work, even if you can’t choose work versus not working overall. I hope this experience can be available to everyone, but we all have to understand that the business needs and profit models in place at most companies make it unlikely.

Choosing work versus not-working highlights the elephant in the room. The final complicating factor in our consent journey comes down to money. For the 95% of Americans who are not financially independent, whether you enjoy it or not you must work to gain the money you’ll need to turn around and use to survive and thrive. Working, as a function of acquiring money, is mandatory. If it’s not been mandatory for you, that is a sign of economic privilege and is not a common experience.

If we understand consent as “choosing what your body experiences” and agree that most people do not get to choose if they experience work or not, it follows that there is a consent issue at the core of working jobs delightful to horrific.

Intersections matter

In a recent Nation article, JoAnn Wypijewski brings in Black feminist centered intersectionality, investigates knee-jerk policing, and incorporates workaday labor, asking,

“What do we see when we inspect the hydra-head of the working day? When we look unblinking at the embodied experience of people—men, women, trans—wherever they belong to a workforce under control?”

There’s discomfort related to reckoning with the presence of mandatory labor, and it’s extended by intersections of marginality that can – though not necessarily – further reduce one’s work or money options. This in turn reduces the pool of things one can choose among to consent to. De facto, this is why it sucks to experience marginalization: being pushed to the sides is denial of access historically and in the present. For people whose ancestors have been marginalized that can look like generational poverty, which plays out in less wealth to transfer, if any — and more mandatory work. What does it do to a society when consent is a fringe concept, and those most affected by its absence have been denied consent on multiple levels?

Think for a moment what it’s like to be at a job where you’re being sexually harassed (or hell, screamed at by your boss) but you know in the back of your mind that you can quit. Now, think about the same situation but you believe that you can’t quit the job. Money is likely the factor, or a money-related aspect like health insurance, immigration status, career trajectory, or pension/seniority. For the actresses lifting up #MeToo, their loss assessment for stepping out of abusive work situations was fame and livelihood; for many workers it is security and livelihood.

There are tons of people for whom being marginalized doesn’t stop, define, or limit their lives. Being at any identity intersection is not a predetermining factor for any particular kind of life. It is crucial to remember this. We can look to people we relate to, who have been able to carve a path we ourselves might want to follow, to learn how to achieve at least second-order consent: work we choose, even if working is mandatory. It’s lovely to see others with the appearance of choice, albeit confusing if we compare it to our own choices and wonder where we fell down or were let down.

Freedom and the means to choose

Work, worth, options, bills, stuckness, choosing, career, bootstrapping, rent — all swirling around while a cultural chorus raises up consent as the goal to which we must move. I completely agree with that goal but I think a key question is unanswered: how does a society that deeply values freedom and independence balance that its core activity, laboring, has been constructed as a mandatory activity? Workforce unrest, indeed.

Individual freedoms are the clarion call of American mythology that says “Work hard and choose how to live.” These are grounded deeply in Protestant notions of free will and colonialist understandings of property ownership. In late capitalism freedom in the US means we can freely choose among brands, or between a marketing or an accounting profession, but find pragmatic limitations to choosing free-from-work time. We are “free to”, not “free from”, in classical philosophical terms. The open source tech folks describe this as “free as in free choice, not free as in free beer.” The freedom and choice available isn’t to be knocked: rather, our desire is for more choice. Yes in the US we have way more choice when compared to, say, feudalism or monarchism or fascism, but still, without money we lack the means to consent to work.

To consent, to say, yes, one needs to be able to say no. Without the possibility of “no” we enter the realm of compulsory activity and ramifications: themselves often related to money. Do what your boss says or you’ll be fired (and not have money or a career). Pay rent or you’ll be evicted (and not have money to get a new place). Make your partner happy (or make it on your own).

The situations that create our work lives train many people to tamper desire and distance themselves from hoping to experience true consent: the presence of yes. Instead, we may labor in situational consent: good enough given my options. The possibility of really getting to choose and therefore someday consent is a carrot in the rat race through years of work days.

We may have autonomy and options, but that’s not the same thing as a big ol’ YES. At the end of the day, most people have to work in our current economic system, and that’s not something you choose.

The incredible KRS One said in Higher Level, “You either vote for the mumps or the measels / Whether you vote for the lesser of two evils, you vote for evil.” Picking from bad options doesn’t really mean you’re in full choice. Innately we know that choosing from a limited set of options isn’t fully free if we HAVE to choose. If you’re out to dinner and you HAVE to pick from the menu, even if there’s nothing you like, disallowed from walking out of the restauraunt, is that consent?

Choosing “good-enough-for-work-I-guess” is blurry, and the longer one practices doing it the farther away the possibility of choosing feels. Soon enough we forget there are other ways to feel besides compromised.

We forget so much, that when we choose things we don’t really want over and over, the outcome is trauma and spiritual crisis.

I think a lot about labor, choice, and the blur between “I want this” and “I can have this other thing, so it better become what I want” as a white cis woman from a working-class background.

I’ve had access to interesting work as well as plenty of blurry, situational consent moments in my 23 working years. At any given time, would I rather be with my beloveds or contributing my best gifts to my people and the world than, say serving coffee at a register (three years) or administrating a college department (one year) or making edits to textbooks (two years)? Hell yeah, but the path there is littered with choices I had to make. Not working was not an option. And, for the 95% of the US who do not have financial independence, it’s not an option for them.

As we talk about consent and how important it is, I hope that the desire to choose gets listened to: we may not be able to dismantle compulsory labor and trade it up for a society where we can be more choiceful about how we contribute, but that doesn’t make it right. In learning to ask for and expect consent I hope the desire for a better world grows hotter and more urgent.